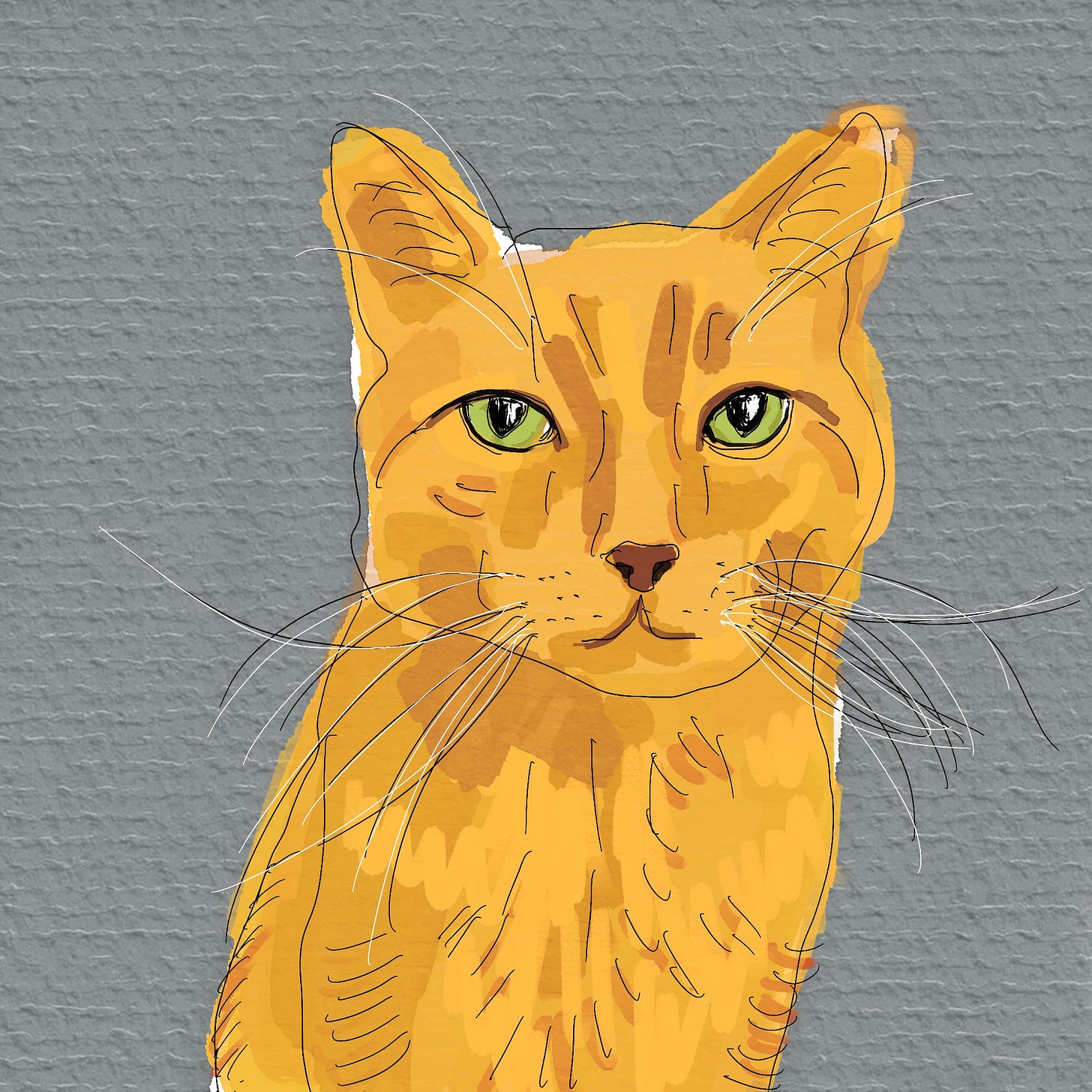

A couple of weeks ago, I held our ailing cat in my arms as a vet injected two drugs into an IV in his paw: one to relax him and the other to stop his heart. Our cat was swaddled in a blanket like a baby. We stroked his head and told him he was a good boy, such a good boy. We looked in his big eyes. Were we making the right decision? Was it the right time? Couldn’t he last even a few more days at home? Did he know what was coming? Did he know we loved him? Was he scared?

It was all so sad and strange and unfamiliar. How we had to hand over our credit card as we held our cat. How we had to decide whether we wanted to pay extra for his paw print, his ashes. How, after we signed the payment screen, the vet tech wished us “a better day.” How we walked out with an empty pet carrier. How we walked into a torrential downpour.

Later I thought, that was not an experience that needs to be defamiliarized. It jolted me out of my daily life and shifted my perceptions. And it got me thinking about other unfamiliar experiences and how powerful it is to encounter them through art.

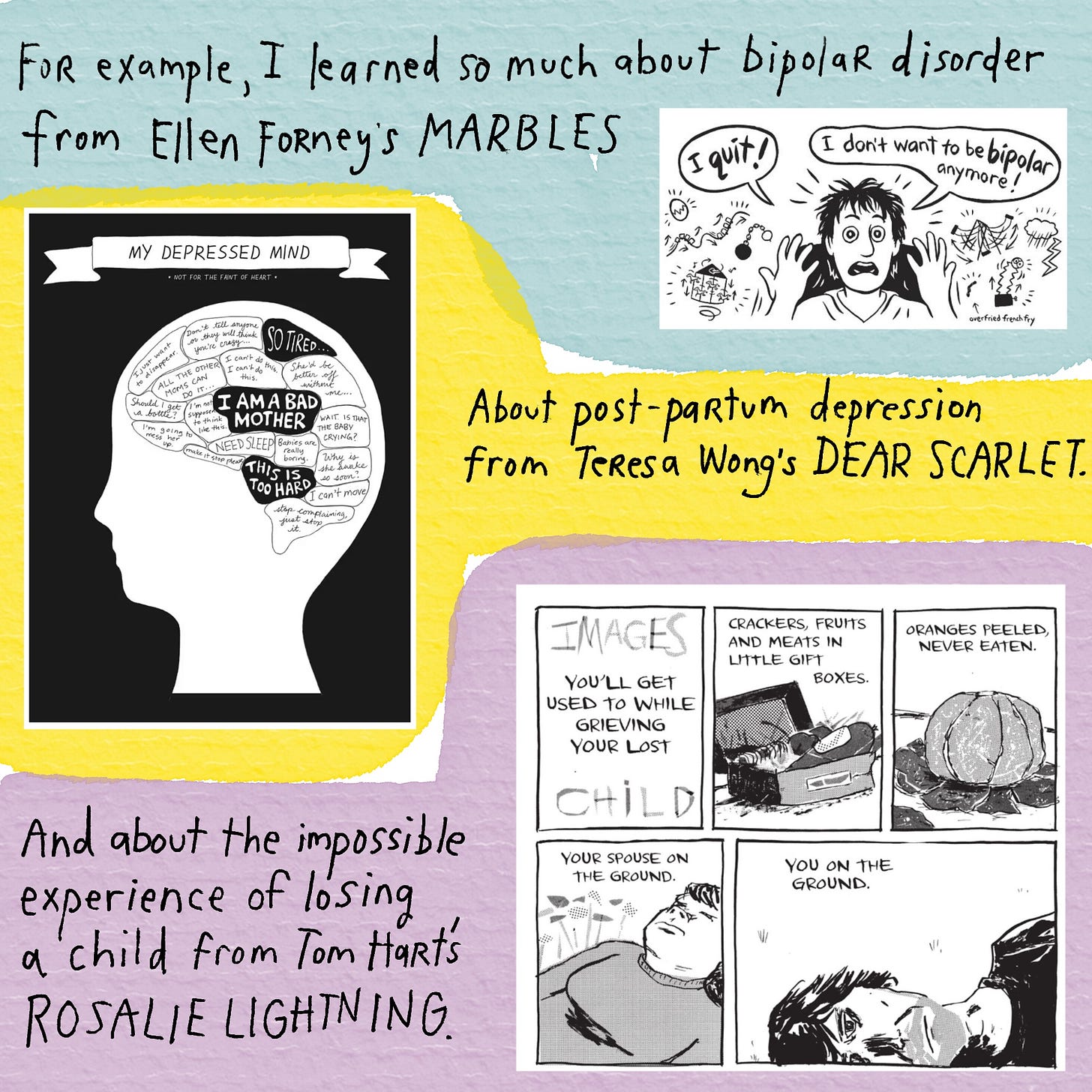

Lisa Cron, author of Story or Die, says we read stories to help us navigate potential futures. By becoming familiar with an experience, even indirectly, we are more prepared to navigate it ourselves: the death of a cat, the loss of a loved one, or even, Cron points out, a saber-toothed tiger attack.

Encountering these unfamiliar experiences in story, Cron says, “allows us to really understand other people,” leading to empathy and human connection. Thus I’ve come to think that familiarization—inviting a reader/viewer into a less familiar experience to them, showing what it feels like and how it changes a person, making the reader feel it too—can be even more important than defamiliarization.

If defamiliarization is the job of the artist, familiarization may be our superpower.

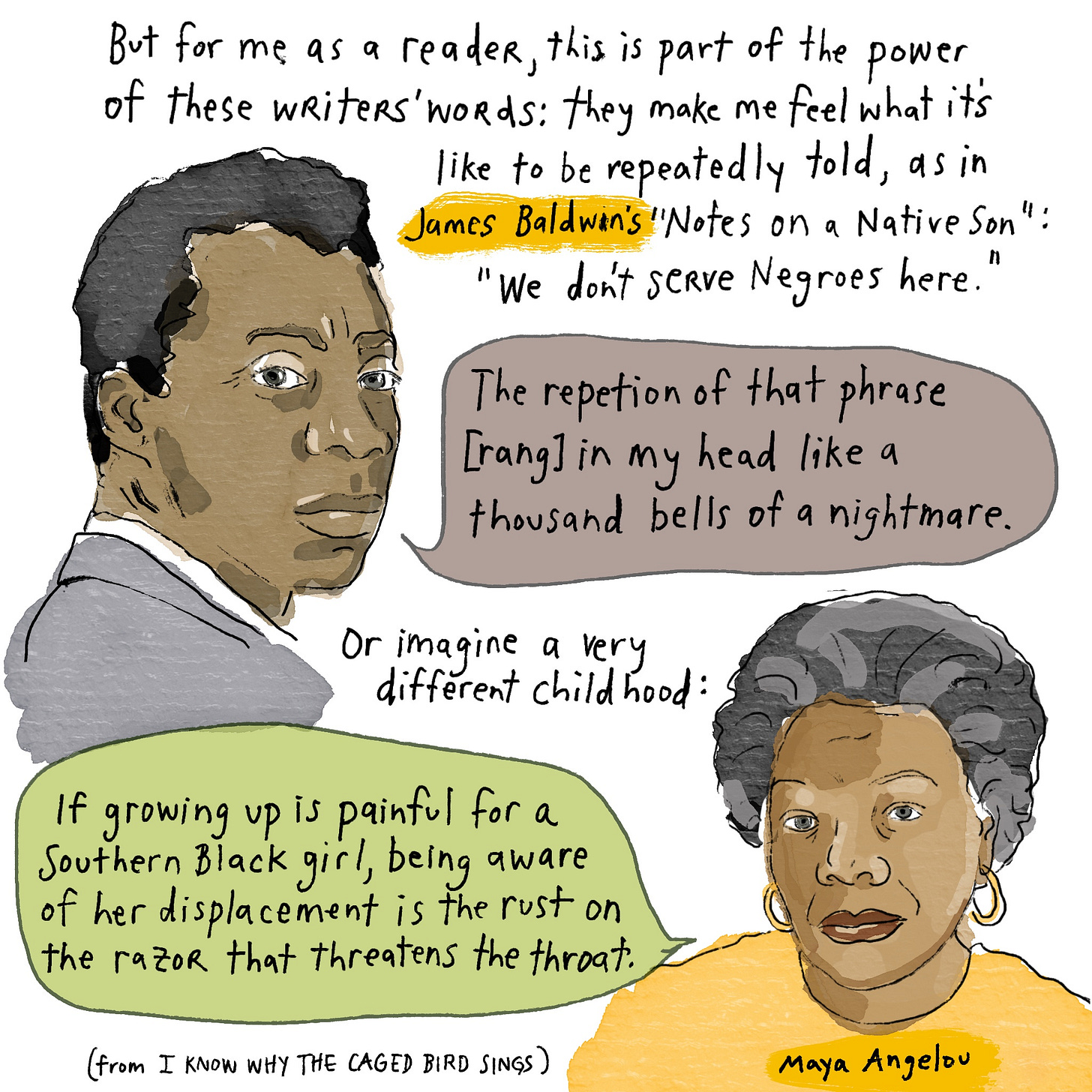

And as a white person, I don’t need the experience of racism to be defamiliarized nearly as much as I need to be familiarized. This is what happens when I read the words of writers like Toni Morrison, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Claudia Rankine, and Ta Nehisi-Coates.

Just to be clear: I don’t mean to say the purpose or goal of their writing is to show a white woman what racism is like. Toni Morrison made it clear that she was writing to and for Black people. And I suspect her books defamiliarize experiences that are all too common for her Black readers.

And, as I start a new semester, I think of the Langston Hughes poem, “Theme for English B,” in which the speaker, “the only colored student in my class,” addresses his white instructor:

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you’re older—and white—

and somewhat more free.This is my page for English B.

This is a good reminder for me of a student’s perspective, and how we all learn from each other.

Yes, artists can defamiliarize everyday experiences by creating poetry, stories, and other art forms that remind us to look and notice. But the artist’s real superpower is making a reader/viewer/listener feel what something unfamiliar is like—and connecting us as humans.

This is so insightful, Kelcey. It is such a challenge that the power of the artist is filled with and, and and, and also this and that and then more and more. It is the gift of the artist to connect those ands and make them into something that is a distinct way beautiful and inspirational.

Arghh. Loved this post so much. So sorry for your loss. Losing a pet is such a hard experience and sometimes we feel like with all the suffering around there is no space for it. So sorry for your loss. You are completely right about reading other people’s experiences. Even if it is to remind us something we already know. Sending you love.